Old fashioned economic stimulus

has a new name for the twenty-first century. Concepts such as Keynesianism,

state intervention and pump priming have been replaced by quantitative easing.

According to

Bob McTeer, quantitative easing is “different from traditional monetary

policy only in its magnitude and pre-announcement of amount and timing.”

And if we accept quantitative

easing is not so very far removed from traditional monetary policy, it merely

becomes the latest in a long line of government economic intervention. Nick

Clegg told

the Liberal Democrat conference last week that Britain should invest its

way out of the downturn. Across the Atlantic, and there are growing demands for

the Obama administration to use the government’s economic heft to create jobs.

This is fuelling the loud

and increasingly antagonistic political debate over how successful fiscal

stimulus policies are, and both proponents and opponents are looking to the

past to reinforce their position.

Since the Second World War, the

US Congress has passed economic stimulus bills during five of the past seven

recessions — in 1964, 1971, 1975, 1981 and 2001. Jason Furman of the Brookings

Institution's Hamilton Project has noted

that measures taken in the 1960s and 1970s were relatively ineffective. This

changed with prompt intervention in 1981, and by 2001 tax cuts came as the US

slid in to recession, rather than following the start of economic recovery.

The Great Depression

and New Deal

The golden age of government intervention came amidst the

economic chaos and social despair of the Great Depression. In the period

starting with the crash of the US stock market on Black Tuesday (29 October

1929) and the inauguration of President Roosevelt (4 March 1933) the US economy

crumpled and confidence evaporated.

Industrial production almost

halved, unemployment sextupled and foreign trade collapsed by 70% as

America stumbled through the darkest days of the depression. Prices slumped by

a third as the US entered a devastating deflationary spiral, compounding the

economic and fiscal pressures. All this combined to give Roosevelt the worst

Presidential inheritance since Lincoln’s receipt of a fracturing union in 1860.

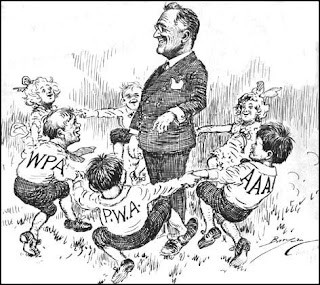

Roosevelt’s policy response was immediate, energetic and

arguably successful. In his election campaign he had

promised a new deal for the American people, and this was delivered in the

first hundred days of his frenetic administration. The closure and reform of the entire banking

system was followed by federal work programmes (FERA, WPA, CCC and the NRA) and

programmes to revitalise the agricultural sector and the poorest rural areas

(such as the iconic Tennessee Valley Authority). So many acronyms and initialisms

emanated from FDR’s White House that they became known as the ‘Alphabet

Agencies’.

So does the New Deal offer lessons to inform today’s debate

on stimulus? Unfortunately, it can be used as fuel for both sides of the

debate. Proponents argue that the New Deal pushed the US economy into recovery.

Keynesian economists suggest it helped, but did not go far enough (FDR was

still keen to balance the books and was forced into reverses from 1937 by a

resurgent Republican Party).

Opponents suggest the New Deal prolonged

the Depression with Cole and Ohanian stating that “New Deal policies are an important contributing factor to the

persistence of the Great Depression”. They have quantified their theory,

and extrapolated that New Deal policies prolonged the Depression

by seven years. Their findings are echoed by Gallaway and Vedder, who argue

that without the New Deal, the unemployment rate would have been 6.7% instead

of 17.2%. But this interpretation is not without critics, including DeLong, who states

that this work produces "flawed conclusions" based on

"flawed foundations", and the entire foundation "is made out of

mud".

Lincoln’s New Deal

The unprecedented economic hardship of the Great Depression

resulted in unprecedented levels of government intervention. But Roosevelt’s

New Deal was not the USA’s first government stimulus package. Abraham Lincoln

fostered an economic development programme that featured some of the most audacious displays

of governmental involvement.

His administration oversaw

the birth of the First Transcontinental Railroad, linking America from

coast to coast and stimulating the development of vast expanses of her lonely

interior. Under the Pacific Railroad

Act 1862 the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads received generous federal

subsidies of both cash and land, encouraging them to forge ahead with ambitious

line building plans. Lincoln was, according

to Stephen Ambrose, "the best

and most powerful friend the transcontinental railroads ever had."

Grants of land were also the staple of his expansion of

higher education through the foundation of Land

Grant Colleges. This programme led to the establishment of colleges

throughout the US, including prestigious

establishments such as the University of California, MIT, the University of

Vermont, Texas A&M and Cornell University.

Other Lincoln policies included Federal agricultural

improvement programmes, protectionist tariffs which forged the development of

the US steel industry and national control over the banking industry to free

capital for investment. Some claim this set the scene for the rise of US

economic dominance. Others suggest

it precipitated the Panic of 1873.

The birth of

dirigisme and Colbert

Crossing back to the Old World, and it is obvious that state

intervention in the economy is as old as economic life. Whether it is the

ancient Egyptian state

grain stores or fixed price bread and

wheat distribution under the Roman Republic, states have always meddled in

the economy. One of the most concerted attempts to go a step further and direct

economic development was found in France under King Louis XIV.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert was the Minister of Finance of France

from 1665 to 1683 where hard work and thrift made him a respected advisor. He intervened

in industrial policy, establishing the Manufacture

royale de glaces de miroirs (the Royal Glass

Works) to replace dependence on imported Venetian glass. The company

continues to this day as one of France’s leading conglomerates under the name Saint-Gobain S.A.

Colbert established the

French merchant marine, protected the

fledgling Compagnie française des Indes orientales (French East India Company),

reformed medieval guilds and restrictive economic practises and oversaw construction

of the Canal du Midi. He eventually balanced France’s chaotic budgets, and

returned the monarchy to surplus. All of this would be undone in Louis XIV’s

numerous wars of expansion, wrecking Colbert’s carefully nurtured prudence.

Out of all of this the only clear lesson in the history of

economic stimulus is that there is no clear right or wrong. Policy makers are

damned if they do and certainly damned if they don’t.